Diplomacy

Russian Foriegn Minister Sergei Lavrov met with with Ukraine’s Foriegn Minister Dmytro Kuleba in Turkey on March 10th. While Kuleba said he did not have high expectations going into the talks, and concluded by noting that Lavrov appeared to lack the authority to make any commitments, these talks are the most serious to have occurred during the conflict. At least since Zelensky claimed that he attempted to call Putin the day before fighting began only to be left on hold. Previous talks on the Belarussian border included lower-level figures(with the exception of Roman Abramovich who did not seem to know what he was supposed to be doing there). The Russian representative was the Minister of Culture. Lavrov is high-profile, though as a career diplomat he is not drawn from the inner circles of Kremlin power or policy-making. A point Kuleba stressed when he told the media “my impression is he(Lavrov) had no authority to make decisions during these talks.”

The choice of Turkey matters as well. The independence of Belarus is questionable after President Lukashenka allowed Russian forces to occupy his country and launch an invasion of Ukraine from its territory. No one doubts the independence of Turkey or of President Erdogan. Turkey is one of Ukraine’s key military suppliers, and perhaps has done more than anyone other than Poland and the United States to support Ukraine. Erdogan has also had a love-hate relationship with Vladimir Putin, fighting proxy wars against Russia in Syria, Libya, and Armenia, while also flirting with buying Russian air defense systems. As a figure with leverage on both sides and a vested interest in a settlement, Erdogan is the type of person both sides might ask to mediate if they wanted to explore what was on the table. He does not have quite enough leverage to impose a settlement if one side does not want it. If Ukraine wanted a settlement at all costs, they would ask Xi Jinping to mediate as he could impose a settlement on Russia. If Putin truly wanted a settlement at all costs, he would not leak terms publicly, but would likely approach French President Emmanuel Macron. That neither has exercised those options indicates that while both may expect a settlement, they each believe their leverage will increase by allowing events on the battlefield to progress.

It is probably best to interpret the supposed “terms” offered by Putin’s spokesman, Dimitry Peskov in that light as well as Ukraine’s response. There has been a rush to see a message in what Peskov did not say, rather in what he did. If one reads only the second part of Peskov’s “terms”, where he demands that Ukraine “should recognize that Crimea is Russian territory and that they need to recognize that Donetsk and Lugansk [Luhansk] are independent states. And that’s it. It will stop in a moment,” it may sound like the basis for a face-saving “compromise” in which Russia abandons expansive goals such as the annexation of large parts of the Ukraine, or the imposition of a puppet government. That is in part an artifact of those ideas being floated explicitly by non-Kremlin sources, such as Anatoly Karlin, so that they could be read as implicit war aims in Putin’s speech. Compared with such delusions, “settling” for the Crimea and Donbass seems like a face saving compromise which many Western “realists” have rushed to embrace as a great opportunity.

In doing so they ignore the first part of Peskov’s statement. Before he mentions any territorial demands, Peskov insists unconditional surrender is a prerequisite for an agreement. “We really are finishing the demilitarization of Ukraine. We will finish it. But the main thing is that Ukraine ceases its military action. They should stop their military action and then no one will shoot.”

Peskov knows, as does everyone, except, it seems, some overeager Westerners, that any proposal which requires Ukraine to unilaterally agree to an armistice before terms can be agreed is a non-starter. Especially when it includes the term “demilitarization” which strongly implies that a Ukraine which gave up Crimea and the Donbass would still not be free to govern or defend itself except subject to Russian veto under Russian terms. This is not a serious offer.

This is not to say it is a meaningless offer. Over the course of several conversations this past weekend, I became convinced that those close to the Russian leadership probably believe that their logistical problems are temporary, and will largely resolve themselves over the course of 72-96hrs. I do not agree with this. I have already explained why I do not believe any amount of time will save the 40-mile convoy to the northwest of Kyiv. Nor do I agree that time is on the Russian side. But the important thing is the Russians seem to believe it, and I expected they would act on that by trying to buy time either through an operational pause or negotiations.

The operational pause and talks are not mutually exclusive. If the Russian command planned to pause in any event, then the offer of negotiations acts to create the impression that the pause is a political choice, not the result of military necessity. The Russians are trying to arrange cease-fires and humanitarian corridors because they care about civilian deaths, rather than because they cannot press on their offensive. Russian forces around Kyiv and Kharkiv are immobile to give diplomacy a chance to work, not because they cannot move.

Kuleba’s remarks that ““I was surprised to hear it as my assumption is that foreign ministers have the power to make decisions, the power to make deals. But it seems specifically for the first round of talks, Lavrov was not in this position,” should be read in this context. Lavrov was sent both to give the impression talks were taking place, but also to judge the tenor of how the Ukrainians viewed their own situation. The terms offered, and the desperation Kuleba evinced in trying to reach a cease-fire would provide useful intelligence on how Kyiv perceived its own military situation. If Ukraine was primarily interested in humanitarian corridors, especially from Mariupol, the inference would be that Kyiv was concerned with the drain of resources from civilians on the defense of that city, and hence on Ukraine’s ability to effectively conduct military operations. Not with the overall military situation. By contrast, if Ukraine tried to bring up political questions, such as the status of the Crimea, Donbass or NATO membership, then it would mean Kyiv felt they were losing.

The talks then were not useless. They revealed to the Russians that the Ukrainians feel they have little to lose and perhaps something to gain from fighting for at least a bit longer.

If so, expect the “failure” of talks to be the “signal” for an attempted resumption of military operations.

The Poles finally killed the farce which was the effort by the European Union and then the United States to pretend they had an alternative policy to the No Fly Zone they have rejected establishing, and pin the blame for killing it on a Warsaw government they have never liked. The first phase of the operation saw European officials announce that the transfer would take place, with an EU parliamentarian saying the planes would be flying within the hour. A Ukrainian government official then posted on Facebook that Ukrainian pilots were already on their way to pick up the new planes. All of this collapsed when someone asked the Poles.

Once is a fiasco. Twice looks like a scam. Over the weekend, the United States began talking up the prospects of Poland transferring Mig-29s in a plan which would see them swapped for US F-16s. What seemed off about this whole affair was that just as with the European initiative, there were a whole lot of leaks about what the Poles were supposedly doing or requesting, but they all came from the other side. In the first case, it was the Europeans and Ukrainians informing the media what the Poles were doing or saying until the Poles themselves killed it. This time it was US officials. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken went particularly far on Sunday in suggesting that not just the US, but also European countries had agreed, implying very strongly on CNN that it was the Poles whose cold feet was holding this up.

If this was true, then we likely would have seen the Poles haggle over how many jets they would send. Instead, what happened is that the Poles announced publicly, to the media, that they would transfer all 28 of their aircraft to the United States, delivering them to the Ramstein Airbase in Germany.

The use of all, and the choice of a US airbase in Germany, as well as the decision to announce the offer publicly was clearly the Poles refusing to be scapegoated for the failure of the plan. Blinken had said the transfer was a US idea on Sunday, and that the Europeans, by implication the Germans, had already agreed. That merely left the Poles. The Poles, by making the offer, forced both the United States and Germany to publicly admit that, no, the holdup was not with the Poles, but that neither the United States nor Germany ever had the slightest intention of following through on their part of the scheme senior officials of both governments were spending Sunday pushing. Which they have now done.

The Mig-29 deal is now dead. But what the Poles have done is demonstrated it was never alive. It was always intended to create the impression something was being done, while ensuring that nothing happened and someone else took the blame. If Washington and Berlin come off looking unseemly, well that is what they were doing.

Statements by representatives of both India and China have been parsed as if originating from ancient oracles by those looking for some indication that either country is about to abandon their stated positions. This is likely futile. Both have very good reasons for the positions they have adopted, and have been offered few reasons to change them. Narandra Modi is probably the most Pro-American Prime Minister India has ever had, but his efforts have never truly been reciprocated except under Donald Trump. For all the talk of whether Putin would or would not have invaded Ukraine under Trump, the real difference is probably seen in the attitudes of leaders and states who had strong relationships with the previous Administration - Brazil under Bolsinaro, the Gulf parties to the Abraham Accords, and Modi’s India. All would be open to a partnership with Washington, but all have reason to fear the personal hostility of a Democratic Administration which refused to take the calls of the Saudi Crown Prince for months, appears to be preparing to side against Bolsinaro in this falls elections(and perhaps back a military coup if he refuses to leave) and which picked a fight with Modi over domestic affairs less than a month ago. A hard truth: it is hard for the Biden Administration to expect risky political support from leaders it is actively trying to undermine or overthrow domestically. Why Biden should expect MBS to take his calls now when he refused for months is beyond me.

Nonetheless, there has been a shift in tone in their remarks. One vaguely detectable in China as well. This is not a shift in a Pro-US or Ukraine direction. If anything, Chinese media is more militantly anti-American, and Chinese officials more explicit in blaming Washington for the crisis. But there appears to be concern on the progress of the War, and the implications if it continues, or Russia begins to lose.

In contrast to the “West” where a Russian victory poses the primary geopolitical threat, a Russian defeat in the Ukraine and a collapse of the Putin regime poses much greater risks to these states. The longer the war goes on, the more vulnerable Russian forces in Libya and Syria become, potentially triggering a resumption of those conflicts as Russia’s local foes scent blood. For India, which has relied on Russia as a check against the Taliban and Pakistan, a collapse of Russian power greatly complicates New Delhi’s strategic position, especially as one of the reasons for the reliance on Moscow is the perception America is not a reliable partner. As for China, a senior Chinese academic with ties to the party leadership published a rant including “"With the support of Kazakhstan, Nepal, Vietnam, the Philippines, and other countries, the US intends to reproduce the Ukrainian model in Asia and conduct strategic containment of China.” The inclusion of Kazakhstan, where Russia intervened last December, indicates the role Moscow plays in stabilizing the Central Asian states. China, for all the talk of its “rise” has generally avoided physical intervention abroad. A Russian collapse might force them to either contemplate a more direct role, or risk those states drifting back into a Western orbit.

Military

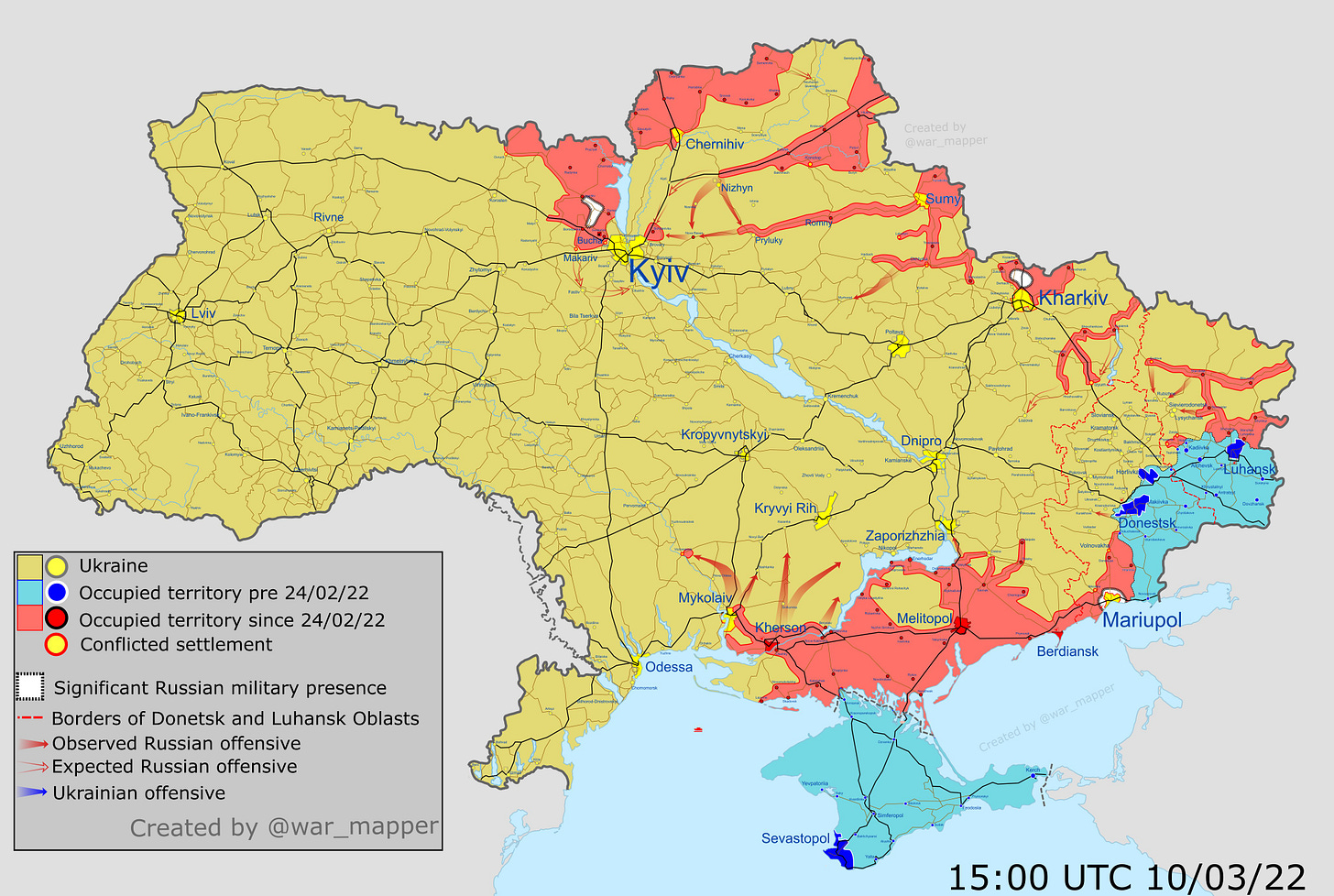

The above map, created by @war_mapper provides some context to the military situation. While it would be inaccurate to say the Russian advance has “stalled” the impending encirclement of Ukrainian forces in the east, which appeared so imminent on Russian maps shared on twitter a week ago, looks a long way off. The real world is not Hearts of Iron 4. Russian forces are moving far too slowly, and with far too thin screens to accomplish that sort of move. If it occurs, it will be because Ukrainian forces in those areas are immobile as they were in Mariupol. Not because Russian units are moving too fast.

There has been extensive discussion of the Russian recourse to bombardment, both by missiles and artillery, as either a political response to frustration, or as some sort of doctrine established in Syria. More likely, it is a consequence as it was for the Bosnian Serbs in the 1990s of a lack of reliable, trained infantry. The Russians have infantry, including conscripts, paramilitaries, the Chechens etc, but as the Bosnian Serbs found, there is a different between thugs with guns and infantry capable of carrying out dangerous and tactically sophisticated operations as opposed to occupying territory and terrorizing local civilians. The easiest explanation for why Russian tanks lack an infantry screen is that the Russian army lacks the infantry to provide them. The easiest explanation for why the Russian army is not attempting to storm prepared positions, except in cases where mobile forces encounter only local Ukrainian territorial troops in the south is because the Russians only have the infantry to launch assaults in one or two places at once.

In the longer term this poses a problem for Moscow. Much of the analysis of the conflict assumes that Moscow is the side with superior numbers, and greater reserves, but in practice the opposite may be true. While Russia can theoretically call upon much greater manpower reserves, the performence of conscripts hitherto implies they are tactically worthless. Bringing up another 80,000-120,000 would not provide any increase in the Russian army’s infantry capable of undertaking assaults or combined operations when the existing conscripts and reserves have so far proven unable to conduct such operations.

By contrast, the longer the conflict goes on, the more time Ukraine has to call up reserves. More than 400,000 Ukrainians rotated through action in the Donbass over the last eight years, providing a larger operational reserve than the Russian army possess. Combined with a greater pool of motivated volunteers, the challenge for Kyiv will be equipping these forces. Infantry weapons, unlike aircraft, are relatively easy for NATO to supply.

There is a reason to believe therefore that the Ukrainian army will find it much easier to increase its defensive power than the Russian army will to increase its offensive potential. That is not to say that the Russian army’s offensive potential is in anyway exhausted. But there is a reason the advance has slowed down and shifted to a firepower-heavy approach.